What started out to be a brief outline of Polish history morphed

into this rather lengthy timeline. The more I read about Poland, the more

fascinating the story became to me. It really is quite an interesting story.

I hope you will enjoy it as well!

Prehistory: Human habitation in the area now known as Poland has been dated as far back as 2300 BC. knowledge of these times is limited, since few written ancient and medieval sources are available. Written language came to Poland only after 966 AD, when the ruler of the Polish lands converted to Christianity and educated foreign clerics arrived

700's: The Polans (also known as Polish: derived from Old Slavic pole, meaning "field" or "plain") were a West Slavic tribe inhabiting the Warta River basin of the historic Greater Poland region in the 8th century.

800's: In the 9th century, the Polans united several West Slavic groups, which ultimately developed into the Kingdom of Poland.

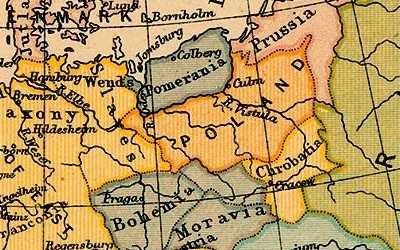

Poland in 912

(click any map to enlarge)

960-992: Mieszko I becomes tribal ruler after the death of his father. He ruled until 992 and is credited with the Unification of Polish lands. Mieszko's state was the first state that could be called Poland. He is often considered the founder, the principal creator and builder of the Polish state. During his reign, Mieszko's acceptance of Roman Catholicism is directly responsible for the inclusion of his country in the mainstream civilization and political structures of Roman Catholic Europe. This is known as the Baptism of Poland.

992-1025: Mieszko I was succeeded by his son, Boleslaw I The Brave, who continued to expand the country. Bolesław I was a remarkable politician, strategist, and statesman. He not only turned Poland into a country comparable to older western monarchies, but he raised it to the front rank of European states. Bolesław conducted successful military campaigns in the west, south and east. He consolidated Polish lands and conquered territories outside the borders of modern-day Poland. In 1000, Poland was recognized as a state by the Holy Roman Empire and the Pope.

1025: Duke Boleslaw I the Brave was crowned King of Poland, marking the starting date for the Kingdom of Poland, though for many years the Poles were ruled not by Kings, but by Dukes. During this same year, Boleslaw died and was succeeded by his son Mieszko II Lambert.

Kingdom of Poland in 1097

1138: Upon the death of Duke Boleslaw III, according to his Last Will and Testament, Poland was divided up among his four sons. By issuing it, Bolesław planned to guarantee that his heirs would not fight among themselves, and would preserve the unity of his lands. However, he failed; soon after his death his sons began to fight each other. This weakened Poland and resulted in a period of fragmentation lasting about 200 years

1226: One of the regional dukes, Konrad I, invited the Teutonic Knights to help him fight the Baltic Prussian pagans. Konrad's move caused centuries of warfare between Poland and the Teutonic Knights, and later between Poland and the German Prussian state. The Prussian inhabitants defended themselves tenaciously, but by 1283 they had been crushed.

1295: Attempts to reunite the Polish lands gained momentum in the 13th century, and in 1295, Duke Przemysł II of Greater Poland managed to become the first ruler since Bolesław II to be crowned king of Poland.

1308: The Teutonic Knights seized Gdańsk and the surrounding region of Pomerelia. Much of this area was lost to Poland for centuries to come.

1386: A personal union between Poland and Lithuania began for the purpose of defense against the Teutonic knights.

Poland in the 14th Century

showing land lost to the Teutonic Knights and

the close relationship with Lithuania

1410-1640: The Reformation: Protestant Reformation movements made deep inroads into Polish Christianity and the resulting Reformation in Poland phenomenon involved a number of different denominations. The policies of religious tolerance that developed were nearly unique in Europe at that time and many who fled regions torn by religious strife found refuge in Poland.

1410: Poland and Lithuania forces defeated the Teutonic Order at Tannenberg.

1411: The First Peace of Torun formally ended the war between Poland-Lithuania and the Teutonic Knights. However, the treaty was fundamentally weak and left the knight's territory virtually intact. However, large war reparations were a significant financial burden on the Knights, causing internal unrest and economic decline. The Teutonic Knights never recovered their former might.

1454: Casimir IV issued a manifesto incorporating the Prussian Provinces with Poland. This led to the Thirteen Years' War with the Teutonic Order.

1466: Second Peace of Torun ends the war with the Teutonic Order. In the treaty, the Teutonic Order ceded the territories of Eastern Pomerania including Danzig, Kulmerland including Kulm and Thorn, the mouth of the Vistula including Elbing and Marienburg, and the region of Warmia including Allenstein (Olsztyn). The Order also acknowledged the rights of the Polish Crown for Prussia's western half, subsequently known as Polish or Royal Prussia. Eastern Prussia, later called Duchy of Prussia remained with the Teutonic Order until 1525, as a Polish fief. The defeat of the Knights raised up a new enemy on the eastern frontiers of Poland - the Russians.

1525: The Teutonic Order was ousted from East Prussian territory when its own Grand Master, Albert, adopted Lutheranism and assumed the title of duke as hereditary ruler under the overlordship of Poland. The area became known as the Duchy of Prussia.

1543: Nicolaus Copernicus, mathematician and astronomer born in Torun, formulated his model of the universe that placed the Sun rather than the Earth at the center of the universe.

mid-1500's: The Polish Constitution assumed the form that would last until the First Partition in 1772. The chief power in the state had formerly been in the hands of the magnates and princes, but was now extended to the large body of nobles and petty landowners, called the szlachta. The King was elective, and was Commander-in-Chief of the Army, but he could not touch the life, liberty, or property of the nobles. The King was helped to govern by a Senate and by a Diet of elected deputies. The Diet met irregularly and decisions had to be unanimous. The Roman Catholic Church wielded considerable power, and supported the King against the disruptive tendencies of the szlachta. Non-Roman Catholics were called Dissidents. Polish intolerance towards the Dissidents continued to increase and played into the hands of the Prussians and Russians, which helped contribute to the Partitions. The peasants, comprising the mass of the population, were completely under the jurisdiction of the lords of the manor; but unlike Russian peasants, they could hold land and could not be sold.

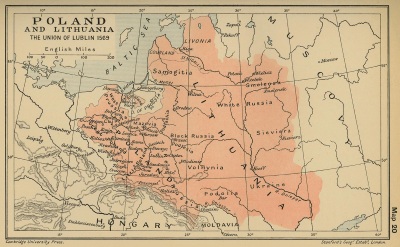

1569: Polish-Lithuanian Commonweath. The personal union between Poland and Lithuania officially became a political union by the Union of Lublin. The single state was known as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonweath, and was ruled by a single elected monarch. This effectively doubled the size of Poland. Royal Prussia lost its autonomy and was united with the Polish Crown. By joining forces, Poland and Lithuania were able to check Russian aggression and a recurrence of German hostility in the Baltic.

1569 Map of Polish-Lithuanian Commonweath

1573: Henry of Anjou elected king. The choice of Henry was the first instance of the danger to the country involved by a system of election which was not confined to Poles (Lithuanians also voted). The Poles realized the danger, and in countering it with legal reforms, practically stripped the central authority of most of its power. Henry's reign would only last 2 years.

1575: Stephen Batory elected king. Under his reign was a fairly successful attempt to form a stronger monarchy, supported by the Roman Catholic Church. He would reign until 1586

1587: Zygmunt III becomes king. He would rule for 45 years. Like his predecessor, Zygmunt supported the Roman Catholic Church as the one power left which was capable of checking the disruptive tendencies of the Reformation and the disorderliness of the nobles. Zygmunt tried to reform the Polish Constitution by substituting the decision of all matters by a plurality of votes instead of by a unanimity impossible to obtain. But the opposition of the magnates, backed by the szlachta, was too strong.

Zygmunt III

1592: After creating a personal union between the Commonwealth and Sweden, Zygmunt III was crowned king of Sweden, in addition to being King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

1599: Zygmunt III was deposed as King of Sweden during the Swedish civil war by his uncle Charles IX. Zygmunt would spend most of the rest of his life trying to regain the Swedish throne.

1600: Polish-Swedish War of Succession began; also known as the 2nd Polish-Swedish War. It would last for 29 years with short periods of truce in between.

1618: Duchy of Prussia (East Prussia) was inherited by the Elector of Brandenburg after Albert Frederick passes with no heirs, forming Brandenburg-Prussia. The Thirty Years War begins, a series of wars in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648. It was one of the longest, most destructive conflicts in European history. Initially a war between Protestant and Catholic states in the fragmenting Holy Roman Empire, it gradually developed into a more general conflict involving most of the great powers of Europe, becoming less about religion and more a continuation of the rivalry for European political pre-eminence.

1629: The Truce of Altmark was signed on October 26, 1629, ending the 2nd Polish-Swedish War. Though the Poles were far from defeated, Sweden generally got the better of Poland in the truce. Poland ceded Livonia (today's Latvia and Estonia) to Sweden, along with many of the cities in Royal and Ducal Prussia. Sweden was also given the right to tax Poland's trade on the Baltic. This was a shortcoming of Poland's diplomatic efforts, not its army.

1632: Zygmunt III died of a stroke on April 30th. He was succeeded by his son, King Wladyslaw IV. During his reign, Wladyslaw attempted to strengthen the Polish throne. However, the szlachta became jealous of his efforts and devoted themselves to thwarting every scheme of the King.

1635: After the death of Sweden's King Adolphus, and after being weakened in the Thirty Years War, the Truce of Altmark was revised in Poland's favor. The Swedish tax was removed, and Sweden withdrew from many of its Baltic ports.

1640: Rule over Duchy of Prussia passed by inheritance to Frederick William, the "Great Elector". Prussia was secured and organized by Germans under the control of the Order.

1648: King Wladyslaw IV died of an infection related to kidney stones on May 20, 1648. Having no legitimate male heirs, he was succeeded by his half-brother John Kasimir II. Wladyslaw's death marked the end of relative stability in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, as conflicts and tensions that had been growing over several decades came to a head with devastating consequences.

1648: Cossack Rebellion began when Cossacks, Tatars, and local peasants started an uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonweath in the areas of present-day Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, and parts of Russia. The insurgency was accompanied by mass atrocities committed by Cossacks against the civilian population, especially against the Roman Catholic clergy and the Jews. The success of anti-Polish rebellion, along with internal conflicts in Poland as well as concurrent wars waged by Poland with Russia and Sweden, ended the Polish Golden Age and caused a secular decline of Polish power during the period known in Polish history as the Deluge.

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1648

1654: The Russian army invades Poland, igniting the Thirteen Years War. Russia had been a supporter and supplier to the Cossacks in their rebellion against the Polish monarchy. Seeing an opportunity with the weakened Polish state, Russia took advantage and the Commonwealth initially suffered several defeats.

1655: Charles X of Sweden invaded and occupied western Poland–Lithuania, the eastern half of which was already occupied by Russia. This was known as the Second Northern War. Poland-Lithuania was now fighting wars on two fronts, as well as internal rebellion.

1657: The Treaty of Wehlau: Frederick William, Duke of Prussia, promised to provide 6,000 troops to Kasimir II for use in the war against Sweden. In return, Kasimir recognized Frederick William and his heirs as sovereign rulers of Duchy of Prussia (East Prussia).

1660: The Treaty of Oliva ended the Polish-Sweden War and confirmed the provisions of the 1657 Treaty of Wehlau. With the end of the Polish-Sweden War, John Kasimir II was able to turn his full attention to the war with Russia. He was able to regain most of the land he had previously lost to the Russians.

1667: The Truce of Andruszowo was signed, ending the Thirteen Years War between Russia and Poland. Despite military victories, the plundered Polish economy was not able to fund the long conflict. Facing internal crisis and civil war, Poland was forced to sign a truce. The war ended with significant Russian territorial gains and marked the beginning of the rise of Russia as a great power in Eastern Europe.

1668: John Kasimir II, grief-stricken over his wife's death, abdicated the throne of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. His reign was one of the most disastrous in the history of Poland. He was succeeded by Michael Wisniowiecki, who became known as Michael I.

1672: The Ottoman Empire (Turkey) declared war on the Commonwealth and invaded from the south in June, beginning the Polish-Ottoman War. In October, Michael I was pressured to sign the Treaty of Buchach, by which Podolia (present-day southern Ukraine) was ceded to the Ottomans. However, the Polish sejm (lower house of parliament) never ratified the treaty, and hostilities were resumed less than a year later.

1673: King Michael I died on November 10, 1673 of severe food poisoning, although it is also believed that he was poisoned by his closest supporters and generals due to the declining power of the Commonwealth. Michael's reign was considered to be less than successful as his ability to be a capable monarch were greatly hurt by Poland's quarrelling factions.

1674: John III Sobieski is elected King of the Poland-Lithuanian Commonwealth replacing the deceased Michael I. He had not wanted to be king, but was elected as a protest vote. Some influential Lithuanian magnates had tried to introduce a bill earlier in the year which would have prohibited native Poles from running in the election. Sobieski was a Polish military hero, and thus the Poles rallied behind him and elected him King. Sobieski became a king of a country devastated by almost half a century of constant war. The treasury was almost empty and the court had little to offer the powerful magnates, who often allied themselves with foreign courts rather than the state.

1676: Treaty of Zurawno was signed between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire ending the Polish-Ottoman War. While this treaty was somewhat more favorable to Poland than the 1672 Treaty of Buchach, the Ottomans still retained the region of Podolia. Once again, the Polish sejm refused to ratify the document. Soon afterwards, the Great Turkish War broke out between Turkey and several European powers. Not until 1699 was the fate of Podolia settled, when the Ottoman Empire was forced to return it to Poland after losing the Austro-Ottoman War.

1683: Conscious that Poland lacked allies and risked war against most of its neighbors (similar to the Deluge), Sobieski allied himself with Leopold I, of the Holy Roman Empire. The alliance was signed by royal representatives on 31 March 1683, and ratified by the Emperor and Polish parliament within weeks. Although aimed directly against the Ottomans and indirectly against France, it had the advantage of gaining internal support for the defense of Poland's southern borders. Meantime, in the spring of 1683, royal spies uncovered Turkish preparations for a military campaign. Sobieski feared that the target might be the Polish cities of Lwów and Kraków. Sobieski's greatest success came later in 1683, with his victory at the Battle of Vienna, in joint command of Polish, Austrian and German troops, against the invading Ottoman Turks.

1696: King John III Sobieski died of a sudden heart attack. He is considered one of the most notable monarchs of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Sobieski's military skill, demonstrated in wars against the Ottoman Empire, contributed to his prowess as King of Poland. Sobieski's 22-year reign marked a period of the Commonwealth's stabilization, much needed after the turmoil of the Deluge and the Cossack Uprising. Popular among his subjects, he was an able military commander, most famous for his victory over the Turks at the 1683 Battle of Vienna. After his victories over them, the Pope called him the savior of Christendom.

1697: Augustus II was elected King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in a controversial election. Another candidate had actually received more votes! However, Augustus II was able to physically take charge earlier than the other candidate and became King. Augustus had been backed financially by Russia and Austria. This would be the last "free" election in Poland for almost 300 years. Subsequent elections would be held under the control of foreign governments.

1700: The Great Northern War began when a coalition made up of Poland, Russia, Saxony (present-day Germany), Denmark, and Norway declared war on the Swedish Empire and launched a three-fold attack.

1701: Duchy of Prussia (East Prussia) elevated to Kingdom of Prussia under King Frederick, Elector of Brandenburg

1704: A series of Swedish victories over Poland resulted in Sweden dethroning Augustus II and installing Stanislaw Leszczynski as King of Poland, thereby tying the Commonwealth to Sweden. Augustus II then teamed up with Russia and initiated military operations in Poland against Sweden.

1706: King Charles XII of Sweden continued to gain ground in Poland, eventually forcing Augustus II to renounce his claims to the Polish throne. Stanislaw Leszczynski was now the undisputed King of Poland, known as Stanislaus I.

1709: After Russia drives Sweden out of Poland, Augustus II is returned to the throne. By this time, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was so weakened militarily and economically that it had become virtually a protectorate of Russia. The Russo-Swedish War would continue until 1721, much of it fought on Polish territory, further weakening the Commonwealth.

Kingdom of Poland 1730

1733: King Augustus II died in Warsaw. As King of Poland, his reign was considered successful. He led the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the Great Northern War, which led to the Russian Empire strengthening its influence with the Commonwealth. He achieved internal reforms with his admired wit that led to an enlightenment among Poland at the time, and he bolstered royal power in the Commonwealth.

1734: Augustus II's eldest son, Frederick Augustus of Saxony, is installed as the new King of Poland by the Russian Army. This led to the Polish War of Succession, a military campaign outside of Poland's borders between various European powers over who would be King of Poland. The alternative candidate was none other than the former king, Stanislaus I. The war would last 5 years, and at the end, Frederick Augustus was confirmed as Poland's king, becoming Augustus III.

1763: King Augustus III died. His rule deepened the anarchy in Poland and increased the country’s dependence on its neighbors. As King, Augustus was uninterested in the affairs of his Polish–Lithuanian dominion, focusing instead on hunting, the opera, and his collection of artwork. He spent less than three years of his thirty-year reign actually in Poland, where political feuding paralyzed the Sejm. Augustus III delegated most of his powers and responsibilities in the Commonwealth. The Russian Empire, which had assisted him in his bid to succeed his father, prevented him from installing his family on the Polish throne.

1764: A Russian supported coup d'état resulted in the election of Stanislaw August Poniatowski as king of the Poland-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Reigning under the name Stanisław II, Poniatowski was the son of a powerful Polish noble and the lover of Catherine the Great of Russia. As such, he enjoyed strong support from that Empress's court.

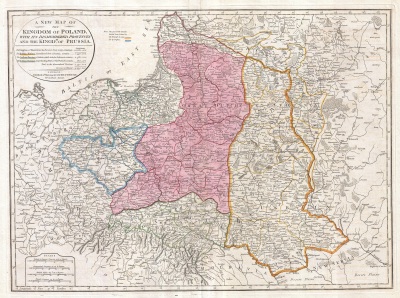

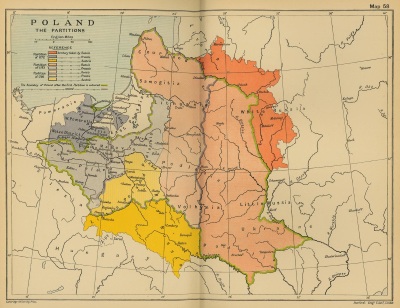

1772: First Partition of Poland: Russia, Prussia, and Austria, all of whom had been steadily occupying more and more Polish territory, entered into a treaty partitioning off the parts of Poland occupied by the three countries. Poland lost nearly a fifth of her population and a fourth of her territory. Prussia obtained Polish or "Royal" Prussia (except the cities of Danzig and Torun), effectively removing Poland's only outlet to the Baltic. Russia took eastern Poland. Austria took southern Poland, removing Poland's only other natural frontier. Poland was too exhausted to resist and the treaty was ratified in 1773. Afterwards, Russia imposed on Poland a new Constitution, further weakening the King and strengthening the nobles.

1773: Prussian king Frederick the Great incorporated the newly-annexed Royal Prussia into the Province of West Prussia, under German rule. He then brought an estimated 300,000 German colonists into the Province.

1791: With Russia occupied with a war on Turkey, Poland attempted to create a new Constitution restoring privileges to the King, increasing his powers, and granting religious liberty, among other things. The success of the new Constitution depended on Russian acquiescence. However, Russia was opposed and in fact, was determined to crush Poland.

1792: A minority group of Poles who opposed the new Constitution, formed a confederacy and appealed to Russia for military intervention. Russian troops entered Poland and occupied Warsaw. King Stanislaw II went over to the Russian side. Most of the ministers responsible for the 1791 Constitution fled the country. The Polish Commander in Chief resigned his command, and the 1791 Constitution was abolished.

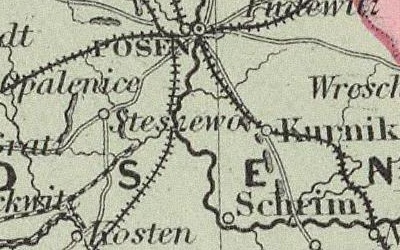

1793: Second Partition of Poland: Exerting their influence, Russia and Prussia agreed to a further partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Prussia gained the cities of Danzig and Torun, as well as much of western Poland including Poznan. Russia acquired half of Lithuania. Poland was left with a third of her original territory. The First Partition had been justified to a certain extent by the existence of anarchy in Poland; the Second was brazen robbery of a helpless neighbor. The Prussian Treaty was the far more difficult of the two for Poles to swallow. While the Russians grabbed land occupied mostly by Russians or Lithuanians, the Prussian land grab was the cradle of the Polish race, and the Polish state as such could not survive its loss. However, Russian and Prussian troops forced the ratification of the treaties.

Poland in 1794 after the Second Partition

The pink area is all that remains of independent Poland

Poznan Province is now a part of Prussia

1794: A "people's rebellion" was formed in Krakow under Tadeusz Kosciuszko and war was declared on Russia. Preliminary success enabled a Provisional Government to be set up in Warsaw. But the Prussians took Krakow, and then joined the Russians in besieging Warsaw. Austria, seeing opportunity, then declared war on Poland. Kosciuszko found himself threatened on three sides. By October, he was completely defeated and surrendered. Kosciuszko was imprisoned. Interestingly, in 1776 he had been a decorated colonel in the Continental Army fighting for America in the American Revolution.

1795: Third Partition of Poland: Russia, Prussia, and Austria completed the final destruction of the Polish state. Frederick William II of the Kingdom of Prussia annexed what was left of the Polish heartland including Warsaw, naming it New East Prussia. Russia grabbed what remained of Lithuania, and Austria grabbed sizable lands in the south of Poland, including Krakow. Independent Poland was now extinct and would remain so for 123 years. The Polish language was abolished as an official language and German introduced. Poles were portrayed as "backward Slavs" by Prussian officials who spread German language and culture. The lands of Polish nobility were confiscated and given to German nobles. In doing all this, a strong national consciousness was recreated in Poland, which from henceforth attained a unity hitherto unknown. Although no sovereign Polish state existed between 1795 and 1918, the idea of Polish independence was kept alive throughout the 19th century. There were a number of uprisings and other military conflicts against the partitioning powers.

1795 after the Third and final Partition of Poland

Poland no longer exists, it's territory split among Russia, Austria, and Prussia.

It would remain this way until the end of World War I.

1806: France, behind Napoleon, invaded Prussia and destroyed its army in a mere 19 days.

1807: Napoleon continued his trek westward defeating the Russians and driving them out of Poland altogether. With the Treaty of Tilsit, the Duchy of Warsaw, a small semi-independent state, was established, which was totally dependent on France. The duchy consisted of lands previously seized by Austria and Prussia; its Grand Duke was Napoleon's ally, the King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony. Its creation met the support of both local republicans in partitioned Poland, and the large Polish diaspora in France, who openly supported Napoleon as the only man capable of restoring Polish sovereignty after the Partitions of Poland of late 18th century. Although it was created as a satellite state (and was only a duchy, rather than a kingdom), it was commonly hoped and believed that with time the nation would be able to regain its former status, not to mention its former borders.

1811: Under Napoleon's rule, serfs in West Prussia were emancipated. Every Prussian subject gained freedom to choose his dwelling-place and his career.

1812: The Russians strongly opposed any move toward an independent Poland and one reason Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812 was to punish them. He made it as far as Moscow before the Russian winter, a lack of supplies, and Russian guerilla warfare dealt his army a catastrophic blow. Following his loss, the Grand Duchy of Warsaw was occupied by Prussian and Russian troops until 1815.

1815 Congress of Vienna: Following Napolean's defeat, Prussia, Russia, and Austria, divied up Polish territory again, also known as the fourth partition of Poland. The Grand Duchy of Warsaw was dissolved and replaced with a new Kingdom of Poland, joined to the Russian Empire. Four-fifths of the Poland of 1772 was now under Russian rule, with the remaining fifth being almost equally divided between Prussia and Austria. However Napoleon's impact on Poland was dramatic, including the Napoleonic legal code, the abolition of serfdom, and the introduction of modern middle class bureaucracies.

1824: West Prussia and East Prussia combined to form the Province of Prussia

1830: The increasingly repressive policies of the partitioning powers led to resistance movements in partitioned Poland, and in 1830 Polish patriots staged the November Uprising. This revolt developed into a full-scale war with Russia, but the insurgents were defeated by the Russian army in 1831.

1840: King Frederick William IV of Prussia sought to reconcile the state with the Catholic Church and the kingdom’s Polish subjects by granting amnesty to imprisoned Polish bishops and re-establishing Polish instruction in schools in districts having Polish majorities.

1862: King Wilhelm I became King of Prussia and he appointed Otto von Bismarck to be Minister President and Foreign Minister. Bismarck favored a 'blood-and-iron' policy to create a united Germany under the leadership of Prussia.

1864: The failure of another uprising in Poland in January of 1863 caused a major psychological trauma and became a historic watershed; indeed, it sparked the development of modern Polish nationalism. The Poles, subjected within the territories under the Russian and Prussian administrations to still stricter controls and increased persecution, preserved their identity in non-violent ways. After the Uprising, the Kingdom of Poland was downgraded in official usage to the "Vistula Land" and was more fully integrated into Russia proper, but not entirely obliterated. The Russian and German languages were imposed in all public communication.

1866: Bismarck invaded and defeated Austria in the "Seven Weeks War", and created the North German Confederation, which included all of East and West Prussia.

1867: restrictions on the movement of peasants was abolished in Prussian Poland

1871: After the French were defeated in the Franco-Prussian War, the German Empire was created with Prussia being the leading and dominating state. Bismarck then proclaimed King Wilhelm I, now Kaiser Wilhelm I, as leader of the new, united Germany (German Reich). Once again, the region was subjected to measures aimed at Germanization of Polish-speaking areas. Bismarck attacked Poles and Catholics together in a rapid succession of laws. This was the beginning of what was known as the Kulturkampf.

1873: Conflict between the Roman Catholic Church and Prussia stimulates patriotic Polonism among Poles. The "May Laws" enacted that the State should control the training and appointment of priests and limit the disciplinary powers of the Church. A royal decree abolished the use of Polish as the language of instruction in both secondary and primary schools. Polish as a subject of study was made optional, whereas before it had been obligatory. Further regulations virtually excluded the Polish language from the administration and the law courts and police courts. The Catholics entirely declined to conform to the new laws.

1878: East Prussia and West Prussia were once again divided and established as separate provinces.

1880: An expected result of the Kulturkampf was the rise in importance of the Polish farming class. Prior to 1871, the farmers status had actually improved and they had not been negatively affected by any of the measures directed against either the landowning class or the Church. In the Kulturkampf, the farmers found themselves attacked for the first time, and attacked in matters of utmost importance to them - namely in their language and their religion. In 1873, there were only 11 farmer's unions in Poznan and West Prussia. By 1880, the number had risen to 120. By 1910, the number would rise to over 300.

1881: Prussian government begins to relent regarding the anti-Catholic laws of 1873. Over the next twelve years, the majority of the anti-Catholic measures were repealed. But the anti-Polish measures remained. All Polish children in national schools continued to receive their education in German, except for religious instruction.

1884: The John and Anna Lewandowski family immigrated to the USA from West Prussia.

1885: The John and Elizabeth Zielinski family immigrated to the USA from West Prussia.

1886 colonization law for Posen and West Prussia: The Prussian Settlement Commission was a Prussian government commission that operated between 1886 and 1924 set up by Otto von Bismarck to increase land ownership by Germans at the expense of Poles, by economic and political means, as part of his larger efforts aimed at the eradication of the Polish nation. The Commission was motivated by anti-Polish sentiment and racism. Land was to be bought from Poles and sold to Germans in districts where a German majority could be created. The Poles organized a counter movement, establishing the Land Bank. The aim of the Land Bank was to purchase land from the Germans and sell it to the Poles. It was so successful that it is estimated that from 1896-1910, the area gained by the Poles from Germans largely exceeded the area gained by the Germans from Poles!

Prussian Poland in 1886

1886-90: The average annual number of emigrants going overseas from West Prussia was 11,283. The great majority of these emigrants went to the United States.

1887: A regulation was secured whereby no teachers of Polish nationality could be employed in Polish districts. Another law was enacted whereby Polish ceased to be a subject of instruction in primary schools. Even private teaching of Polish was prohibited.

1888: Mike Jankowski, son of Constantin immigrated to the USA from the Polish Province of Posen. By 1991, all members of Constantin's family had left Poland forever.

1894: William II upholds Germanism at a speech in Marienburg. German Association of the Eastern Marches is formed to combat Polonism. Its main aims were the promotion of Germanization of Poles living in Prussia and the destruction of Polish national identity in German eastern provinces.

1900: Religious instruction in Polish was completely abolished. Severe measures were taken to secure that all Polish children attended the instruction in German. Despite these regulations, the school policy failed in its main objective, the Germanization of Poles. Combining education and religious reforms gave the national struggle a religious aspect. The Kulturkampf gave the Polish clergy precisely the kind of bond of union with their people which the Catholic Church loves to promote. The Poles gained a body of indefatigable leaders - with a powerful organization behind them - a spokesman and a statesman in every parish.

1906: Prussian Minister of Finance complains that since 1891, Germans in East Prussia have been reduced by 630,000. Nearly 47,000 Polish school children refuse to attend 750 schools in the Province of Posen where the Catechism was being taught in German. Children were punished with detention, while parents were fined or imprisoned for withdrawing their children.

1908: The Prussian diet passed laws permitting the forcible expropriation of Polish landowners in Posen and West Prussia in favor of Germans, and for eliminating the use of Polish language at meetings.

1914: World War I begins. The outbreak of World War I in the Polish lands offered Poles unexpected hopes for achieving independence as a result of the turbulence that engulfed the empires of the partitioning powers. At the start of the war, the Poles found themselves conscripted into the armies of the partitioning powers in a war that was not theirs. Furthermore, they were frequently forced to fight each other, since the armies of Germany and Austria were allied against Russia. Polish territory, split during the partitions, became the scene of much of the operations of the Eastern Front of World War I.

1917: In 1917 two separate events decisively changed the character of the war and set it on a course toward the rebirth of Poland. The United States entered the conflict on the Allied side, while revolutionary upheaval in Russia weakened her and then removed the Russians from the Eastern Front. After the last Russian advance into Galicia failed in mid-1917, the Germans went on the offensive again; the army of revolutionary Russia ceased to be a factor, and Russia was forced to sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in which she ceded all formerly Polish lands to Germany and her allies. The defection of Russia from the Allied coalition gave free rein to Woodrow Wilson, American president at the time, to transform the war into a crusade to spread democracy and liberate the Poles and other peoples from the tyranny of the Central Powers. The thirteenth of his Fourteen Points adopted the resurrection of Poland as one of the main aims of World War I. Polish opinion crystallized in support of the Allied cause.

1918: On 11 November 1918, in Warsaw, Joseph Piłsudski, a hero of the war, was appointed Commander in Chief of Polish forces and was entrusted with creating a national government for the newly independent country. On that very day (which would become Poland's Independence Day), he proclaimed an independent Polish state.

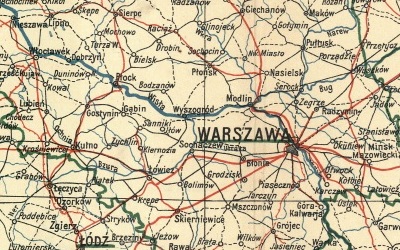

1919: Germany is defeated, ending World War I. After more than a century of foreign rule, Poland officially regained its independence as one of the outcomes of the negotiations that took place at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The Treaty of Versailles that emerged from the conference set up an independent nation with an outlet to the sea, but left some of its boundaries to be decided by plebiscites. This new nation became known as the Second Polish Republic. The Second Republic was significantly different in territory to the current Polish state. It included substantially more territory in the east and less in the west. Peace did not last long. The Polish–Soviet War immediately followed, pitting Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine against the Second Polish Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic over the control of an area equivalent to today's Ukraine and parts of modern-day Belarus.

1920: Polish forces achieved an unexpected and decisive victory at the Battle of Warsaw. In the wake of the Polish advance eastward, the Soviets sued for peace and the Polish-Soviet War ended with a ceasefire in October 1920. A formal peace treaty, the Peace of Riga, was signed on 18 March 1921, dividing the disputed territories between Poland and Soviet Russia. The war largely determined the Soviet–Polish border for the period between the World Wars.

1922: After the Polish Constitution of March 1921 severely limited the powers of the presidency (intentionally, to prevent a President Piłsudski from waging war), Piłsudski declined to run for the office. On 9 December 1922 the Polish National Assembly elected Gabriel Narutowicz as the first President of the Second Polish Republic. He was a controversial choice, and only five days after taking office, on 16 December 1922, Narutowicz was assassinated while attending an exhibit in the National Gallery of Art. Stanisław Wojciechowski was chosen to succeed Narutowicz.

1923: Post-WWI Poland

1926: In the new government, Wojciechowski and military chief of staff Piłsudski disagreed on the political direction of the nation: Wojciechowski supported continued parliamentary government, while Piłsudski favored a more authoritarian approach. In May 1926, due to the worsening economic issues of the country, Marshal Piłsudski staged a successful Coup, and after capturing Warsaw, President Wojciechowski was forced to resign and to give the Marshal a free hand to initiate the "reorganization of the state". Ignacy Mościcki was installed as the new president. He would serve in that capacity until 1939.

1932: Poland signs a non-aggression pact with Soviet Russia, effective for a 3-year period.

1934: In January, the Polish-German Non-Aggression pact is signed with Nazi Germany, effective for 10 years. In December, the Polish-Soviet Non-Aggression pact, due to expire in 1935, was extended without amendment through 1945. Poland, under Chief of State Joseph Pilsudski, had initiated the policy of maintaining an equal distance and an adjustable middle course regarding the two great neighbors.

1935: Chief of State Joseph Pilsudski dies of liver cancer. Pilsudski and President Mościcki had shared power, though in reality, Mościcki was subservient to Piłsudski, never openly showing dissent from any aspect of the Marshal's leadership. After Piłsudski's death, Poland was governed by old allies and subordinates known as "Piłsudski's colonels". They had neither the vision nor the resources to cope with the perilous situation facing Poland in the late 1930s.

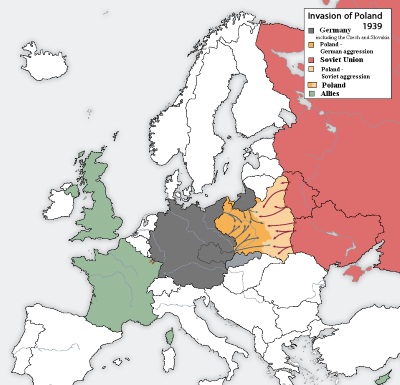

1939: The Second Polish Republic came to an end when Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union and the Slovak Republic, marking the beginning of World War II in Europe. The Nazi invasion began on September 1st, invading from the north, south, and west. Polish forces withdrew from their forward bases of operation to more established lines of defense in the east, where they prepared for a long defense and awaited expected support and relief from her allies, France and the United Kingdom. The two Western powers soon declared war on Germany, but they remained largely inactive (the period early in the conflict became known as the Phoney War) and extended no aid to the attacked country.

The Soviet Red Army's invasion of Eastern Poland on 17 September, in accordance with a secret pact made with Nazi Germany (Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact), rendered the Polish plan of defense obsolete. President Mościcki's government was exiled to Romania on September 17, where he was forced by France to resign his office. A Polish government-in-exile was formed in France, first in Paris, then in Angers, under the protection of France and Britain. Władysław Raczkiewicz was named the new President of the Republic and the government-in-exile, and was recognized by the United Kingdom and, later, by the United States. Raczkiewicz called on Władysław Sikorski to serve as the first Polish prime minister in exile. On November 7th, Sikorski became Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces.

The military campaign ended on 6 October with Germany and the Soviet Union dividing and annexing the whole of Poland. Once again, Poland failed to exist. The Poles formed an underground resistance movement to fight the oppressors, which was loyal to and formally under the Polish government-in-exile. From 1939-45 between 120,000-170,000 Poles and Jews were ethnically cleansed by the Germans. As in all other areas, Poles and Jews were classified as "Untermenschen" by the German state, with their fate being slavery and extermination.

Map showing the invasion of Poland in 1939

First by the Nazis, then by the Russians

1940: Following the Fall of France, the Polish government-in-exile relocated to London. It would remain in the United Kingdom until its dissolution in 1990.

1941: After Germany invaded the Soviet Union as part of its Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, the whole of pre-war Poland was overrun and occupied by German troops. Immediately, the implementation of the Final Solution began, and the Holocaust in Poland proceeded with force.

1943: In April 1943, the Germans announced that they had discovered at Katyn Wood, near Smolensk, Russia, mass graves of 10,000 Polish officers (the German investigation later found 4,443 bodies) who had been taken prisoner in 1939 and murdered by the Soviets. The Soviet government's response was that the Germans had fabricated the discovery. The other Allied governments, for diplomatic reasons, formally accepted this; the Polish government-in-exile refused to do so. The Soviet Union broke off deteriorating relations with the Polish government-in-exile, claiming the Poles had committed a hostile act by requesting that the Red Cross investigate these reports.

On 4 July 1943, while Sikorski was returning from an inspection of Polish forces deployed in the Middle East, he was killed, together with his daughter and eight others, when his plane crashed into the sea 16 seconds after takeoff from Gibraltar Airport. General Sikorski's death marked a turning point for Polish influence among the Anglo-American allies. No Pole after him would have much sway with the Allied politicians. Sikorski had been the most prestigious leader of the Polish exiles and his death was a severe setback for the Polish cause.

The Polish–Soviet crisis was beginning to threaten cooperation between the western Allies and the Soviet Union at a time when the Poles' importance to the western Allies, essential in the first years of the war, was beginning to fade with the entry into the conflict of the military and industrial giants, the Soviet Union and the United States. The Allies had no intention of allowing Sikorski's successor, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, to threaten the alliance with the Soviets. Only four months after Sikorski's death, in November 1943, at Teheran, Churchill and Roosevelt agreed with Stalin that the whole of Poland east of the Curzon Line would be ceded to the Soviets after the war.

1944: After the Teheran Conference, Stalin decided to create his own puppet government for Poland, and a Committee of National Liberation (PKWN) was proclaimed in the summer of 1944. The Committee was recognized by the Soviet Government as the only legitimate authority in Poland, while Mikołajczyk's Government in London, was termed by the Soviets an "illegal and self-styled authority." Mikołajczyk would serve in the Prime Minister's role until 24 November 1944, when, realizing the increasing powerlessness of the government-in-exile, he resigned and was succeeded by Tomasz Arciszewski. Stalin soon began a campaign for recognition by the Western Allies of a Soviet-backed Polish government led by Wanda Wasilewska, a dedicated communist with General Zygmunt Berling as commander-in-chief of all Polish armed forces. By the time of the Potsdam conference in 1945, Poland had been relegated to the Soviet sphere of influence; a total abandonment and betrayal of the Polish government-in-exile by the Western Allies.

The Warsaw Uprising against Nazi Germany began on August 1, 1944. The uprising, in which most of the city's population participated, was instigated by the underground Home Army and approved by the Polish government-in-exile in an attempt to establish a non-communist Polish administration ahead of the arrival of the Red Army. The uprising was originally planned as a short-lived armed demonstration in expectation that the Soviet forces approaching Warsaw would assist in any battle to take the city. The Soviets had never agreed to an intervention, however, and they halted their advance at the Vistula River. The Germans used the opportunity to carry out a brutal suppression of the pro-Western Polish underground. The bitterly fought uprising lasted for two months and resulted in the death or expulsion from the city of hundreds of thousands of civilians. After the Poles realized the hopelessness of the situation and surrendered on 2 October, the Germans carried out a planned destruction of Warsaw on Hitler's orders that obliterated the entire remaining infrastructure of the city. Only after that was completed did the Soviet Red Army advance into Warsaw.

1945: The Soviet-controlled Polish People's Army, fighting alongside the Soviet Red Army, entered a devastated Warsaw on 17 January 1945. Upon defeat of Nazi Germany, all of the areas occupied by the Nazis were restored to Poland according to the post-war Potsdam Agreement, along with further neighboring areas of former Nazi Germany. The vast majority of the remaining German population of the region which had not fled before was subsequently expelled westward. In February 1945, Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt held the Yalta Conference. The future of Poland was one of the main topics that was deliberated upon. Stalin claimed that only a strong, pro-Soviet government in Poland would be able to guarantee the security of the Soviet Union. As a result of the conference, the Allies agreed to withdraw their recognition of the Polish Government-in-Exile, after the formation of a new government on Polish territory. The People's Republic of Poland was founded under Soviet protection and recognized by the United States and the United Kingdom from 6 July. Poland was now effectively a puppet state of Russia. The Polish government-in-exile remained in existence in London, though largely unrecognized and without effective power.

Communist rule and Soviet domination were apparent from the beginning: sixteen prominent leaders of the Polish anti-Nazi underground were brought to trial in Moscow already in June 1945. During the most oppressive phase of the Stalinist period (1948–53), terror was justified in Poland as necessary to eliminate reactionary subversion. Many thousands of perceived opponents of the regime were arbitrarily tried, and large numbers were executed. The independent Catholic Church in Poland was subjected to property confiscations and other curtailments from 1949, and in 1950 was pressured into signing an accord with the government. State-run or controlled institutions common in all the socialist countries of eastern Europe were imposed on Poland, including collective farms and worker cooperatives.

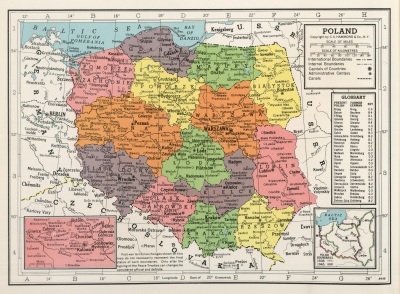

1948: Post-WWII Poland

showing difference between pre-war and post-war boundaries

and the new Provinces

1953: In 1953 and later, despite a partial thaw after the death of Joseph Stalin that year, the persecution of the Church intensified and its head, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, was imprisoned. Among other bishops, he had supported resistance among the Poles towards the Communists.

1956: Amidst continuing social and national upheaval, a further shakeup took place in the party leadership as part of what is known as the Polish October of 1956. While retaining most traditional communist economic and social aims, the regime led by the new Polish Party's First Secretary Władysław Gomułka liberalized internal life in Poland. The dependence on the Soviet Union was somewhat mollified, and the state's relationship with the Church was put on a new footing. A repatriation agreement with the Soviet Union allowed the repatriation of hundreds of thousands of Poles who were still in Soviet hands, including many former political prisoners.

1968: The post-1956 liberalizing trend, in decline for a number of years, was reversed in March 1968, when student demonstrations were suppressed during the 1968 Polish political crisis. Motivated in part by the Prague Spring movement, the Polish opposition leaders, intellectuals, academics and students used a historical-patriotic theater spectacle series in Warsaw (and its termination forced by the authorities) as a springboard for protests, which soon spread to other centers of higher education and turned nationwide. The authorities responded with a major crackdown on opposition activity, including the firing of faculty and the dismissal of students at universities and other institutions of learning. At the center of the controversy was also the small number of Catholic deputies in the Sejm, who attempted to defend the students.

1970: Price increases for essential consumer goods triggered the Polish protests of 1970. In December, there were disturbances and strikes in three port cities, including Gdańsk that reflected deep dissatisfaction with living and working conditions in the country. The activity was centered in the industrial shipyard area of the coastal city. Dozens of protesting workers and bystanders were killed in police and military actions. In the aftermath, Edward Gierek replaced Gomułka as first secretary of the communist party. The new regime was seen as more modern, friendly and pragmatic, and at first it enjoyed a degree of popular and foreign support. In December 1970, the governments of Poland and West Germany signed the Treaty of Warsaw, which normalized their relations and made possible meaningful cooperation in a number of areas of bilateral interest. West Germany recognized the post-war de facto border between Poland and East Germany.

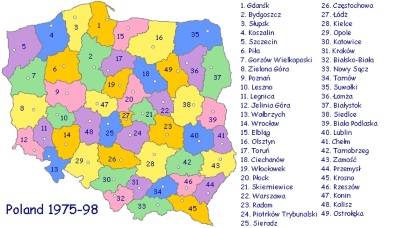

1975: Poland was administratively divided into 49 voivodeships, consolidating and eliminating the intermediate administrative level of counties. An unstated reason for the reform was the desire of the Polish Central Committee to strengthen control over lower layers of the state apparatus. A voivodeship is commonly translated in English as "Province". This division would last through 1998.

Poland's Voivodeships from 1975-1998

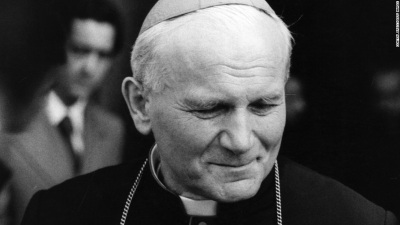

1978: In October 1978, the Archbishop of Kraków, Cardinal Karol Józef Wojtyła, became Pope John Paul II, head of the Roman Catholic Church. Catholics and others rejoiced at the elevation of a Pole to the papacy. Pope John Paul II would serve more than 26 years and become one of the most influential and popular popes in modern history. He would also be instrumental in the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe. Mikhail Gorbachev once said "The collapse of the Iron Curtain would have been impossible without John Paul II."

Pope John Paull II in 1978

1980: Around July 1, 1980, with the Polish foreign debt standing at more than $20 billion, the government made another attempt to increase meat prices. Workers responded with escalating work stoppages that culminated in the 1980 general strikes. In mid-August, labor protests at the Gdańsk Shipyard gave rise to a chain reaction of strikes that virtually paralyzed the Baltic coast. The Strike Committee coordinated the strike action across hundreds of workplaces and formulated a list of 21 demands as the basis for negotiations with the authorities. The Soviet Union proceeded with a massive military build-up along Poland's border in December, but then-General Secretary Stanislaw Kania forcefully argued with Leonid Brezhnev and other allied communists leaders against the feasibility of an external military intervention, and no action was taken. The United States, under presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, repeatedly warned the Soviets about the consequences of a direct intervention, while discouraging an open insurrection in Poland and signaling to the Polish opposition that there would be no rescue by the NATO forces. The Gdańsk workers held out until the government gave in to their demands. On August 31, 1980, representatives of workers at the Gdańsk Shipyard, led by electrician and activist Lech Wałęsa, signed the Gdańsk Agreement with the government that ended their strike. The key provision of the agreement was the guarantee of the workers' right to form independent trade unions and the right to strike. Following the successful resolution of the largest labor confrontation in communist Poland's history, nationwide union organizing movements swept the country. Delegates of the emergent worker committees from all over Poland gathered in Gdańsk on September 17 and decided to form a single national union organization named "Solidarity".

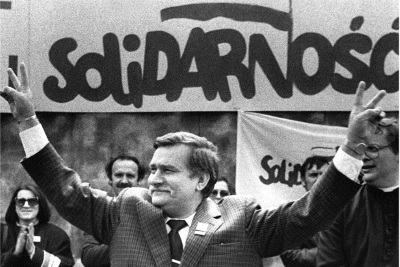

1981: In February 1981, Defense Minister General Wojciech Jaruzelski assumed the position of prime minister. A World War II veteran with a generally positive image, Jaruzelski engaged in preparations for calming the Polish unrest by the use of force, utilizing troops and other security forces backed up by the Polish and Soviet bloc military. The 1980–81 Solidarity social revolt had thus far been free of any major use of force, but in March 1981 in Bydgoszcz, three activists were beaten up by the secret police. A nationwide "warning strike" took place, in which the 9.5-million-strong Solidarity union was supported by the population at large. The Soviets were losing patience. At the first Solidarity National Congress in September–October 1981 in Gdańsk, Lech Wałęsa was elected national chairman of the Union. An appeal was issued to the workers of the other East European countries, urging them to follow in the footsteps of Solidarity. To the Soviets, the gathering was an "anti-socialist and anti-Soviet orgy" and the Polish communist leaders, increasingly led by Jaruzelski, were ready to apply force.

In October 1981, Jaruzelski was named the Communist Party's first secretary, and he kept his government posts. Jaruzelski asked parliament to ban strikes and allow him to exercise extraordinary powers, but when neither request was granted, he decided to proceed with his plans anyway. On December 12, he declared martial law in Poland, under which the army and riot police were used to crush Solidarity. Virtually all Solidarity leaders and many affiliated intellectuals were arrested or detained. Nine workers were killed. The United States and other Western countries responded by imposing economic sanctions against Poland and the Soviet Union. Unrest in the country was subdued but continued.

Lech Walesa in the 1980's

1982: Having achieved some semblance of stability, the Polish regime relaxed and then rescinded martial law over several stages. By December 1982, martial law was suspended, and a small number of political prisoners, including Wałęsa, were released. Although martial law formally ended in July 1983 and a partial amnesty was enacted, several hundred political prisoners remained in jail.

1986: Further developments in Poland occurred concurrently with and were influenced by the reformist leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union (processes known as Glasnost and Perestroika). In September 1986, a general amnesty was declared, and the government released nearly all political prisoners, but the authorities continued to harass dissidents and Solidarity activists.

1988: The government's inability to forestall Poland's economic decline led to the 1988 Polish strikes across the country in April, May and August. The Soviet Union was becoming increasingly destabilized and was unwilling to apply military and other pressure to prop up allied regimes in trouble.

1989: Third Polish Republic established. On August 19, President Jaruzelski asked journalist and Solidarity activist Tadeusz Mazowiecki to form a government; on September 12, the Sejm voted approval of Prime Minister Mazowiecki and his cabinet. For the first time in post-war history, Poland had a government led by non-communists, setting a precedent soon to be followed by many other communist-ruled nations in a phenomenon known as the Revolutions of 1989.

1990: The Constitution of the Polish People's Republic was amended to eliminate references to the "leading role" of the communist party and the country was renamed the "Republic of Poland". The communist Polish United Workers' Party dissolved itself in January 1990, creating in its place a new party, Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland. "Territorial self-government", abolished in 1950, was legislated back in March 1990, to be led by locally elected officials; its fundamental unit was the administratively independent gmina. In October, the constitution was amended to curtail the term of President Jaruzelski. In November, Lech Wałęsa was elected president for a five-year term, becoming the first popularly elected president of Poland.

1999: Poland joined NATO. Elements of the Polish Armed Forces have since participated in the Iraq War and the Afghanistan War. The Polish local government reforms adopted in 1998, which went into effect on 1 January 1999, created sixteen new voivodeships. These replaced the 49 former voivodeships that had existed from 1 July 1975. A voivodeship is commonly translated in English as "Province". Voivodeships are further divided into powiats (counties) and gminas (communes or municipalities).

Poland's Voivodeships effective January 1, 1999

2004: Poland joined the European Union as part of its enlargement in 2004. The NATO and EU memberships were indicative of the Third Polish Republic's integration with the West.

small.jpg)